For all future readings and presentations I do for my new book, Intercede: Saints for Concerning Occasions, I think I’ll start with this disclaimer:

I am a poet, people. Do not mistake me for a medieval scholar, a historian, a theologian, or a religious academic. I am none of those things. So stop asking me hard (though interesting) questions.

Here’s what happened.

I was doing a reading/discussion/book signing at this is a bookstore. Here I am, in the back right corner of this welcoming space listening to Joanna Parzakonis, owner and caretaker introduce me. I’m blissfully unaware of the hard questions that are soon to follow.

One of the poems I read, “A soft, unmuscled God,” was about the gender-bending Saint Wilgefortis. Wilgefortis is the patron saint of trans people, the unhappily married, abused women, and musicians. I told my audience that this medieval saint who never lived was also known by a number of names, like Liberata, Kümmernis, and Uncumber, and that Wilgefortis is the only saint on record that women turned to for losing, rather than gaining, a husband.

First, the poem:

A soft, unmuscled God

A gentle-waisted Jesus,

she hangs on the cross,

two clouds of breasts

billow from her smock.

Cinched in a red bodice

smothered in gold brocade,

Wilgefortis wears a green

gown, though sometimes

it’s royal blue. When it’s cold,

she wears an ermine-lined cloak.

If her wrists weren’t strung

with rope, she’d scratch her

beard, the one that sprouted

from stubbled prayers.

She’d hastily begged God

to make her ugly, the only

way she could think to sheer

the suitor from her side.

She hadn’t fully thought it

through, that when she freed

herself—praise the Lord!—

her pagan, Portuguese King

of a father would bristle

at the sight of a bearded

daughter and crucify her.

It wasn’t so bad the first

few hundred years, when

unhappy wives showered her

with prayers. Desperate

to uncumber from cruel

husbands, they grabbed

hold of Wilgefortis

with her winged hips

and implored her to fly.

Free yourself, Wilgefortis

whispers now as then, but

no one visits these days.

With one shoe off, she hangs,

debunked, bewhiskered,

gloriously broken.

The note

To give people further insight into this most interesting saint who never lived, I then read a goodly portion of the note for this poem that is found at the back of Intercede:

Around 1400, images of this fictitious folk hero—a Jesus figure with beard and sometimes breasts and flaming hips—started cropping up in churches in Germany, France, Spain, Italy, England, and elsewhere. Known as Saint Wilgefortis (from the Latin phrase virgo fortis, meaning “strong virgin”), the English referred to this Christ-like woman as Uncumber. She was particularly popular with unhappily married women, so much so that Saint Thomas More (1478-1535) wrote “they reckon that for a peck of oats she will not fail to uncumber them of their husbands.”

Until I started digging into the lives of saints, I had been a bit judgy and assumed that those living during medieval times were, for the most part, backwards. However, if Saint Wilgefortis is any kind of enlightenment barometer, it seems that the medieval faithful embraced a more complex understanding of the Divine than I realized. People may have connected with this bearded saint and uncovered a way to pray to God precisely because of her gender-blending appearance. Seeing the Christ-like Wilgefortis as genderqueer, genderfluid—or whatever label we might slap on this saint these days—might have felt particularly freeing for women and the LGBTQ community (though they wouldn’t have known or necessarily identified with that label then). Meditating on her story and the image of a Christ-like woman trans-cending her circumstances might have led them to a deeper understanding of God, one that transcends gender and the societal expectations that go with it. Though she is only a legend, my guess is that Saint Wilgefortis uncumbered people from more than just bad husbands.

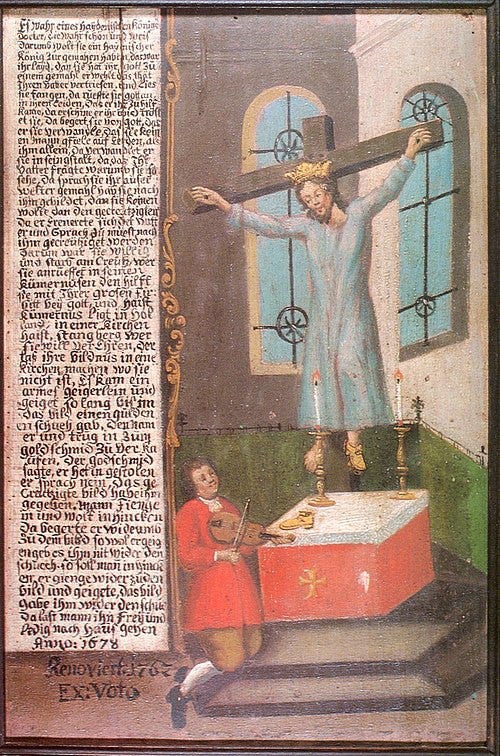

The image

I think at some point I flashed this image that accompanies the poem in the book:

The question

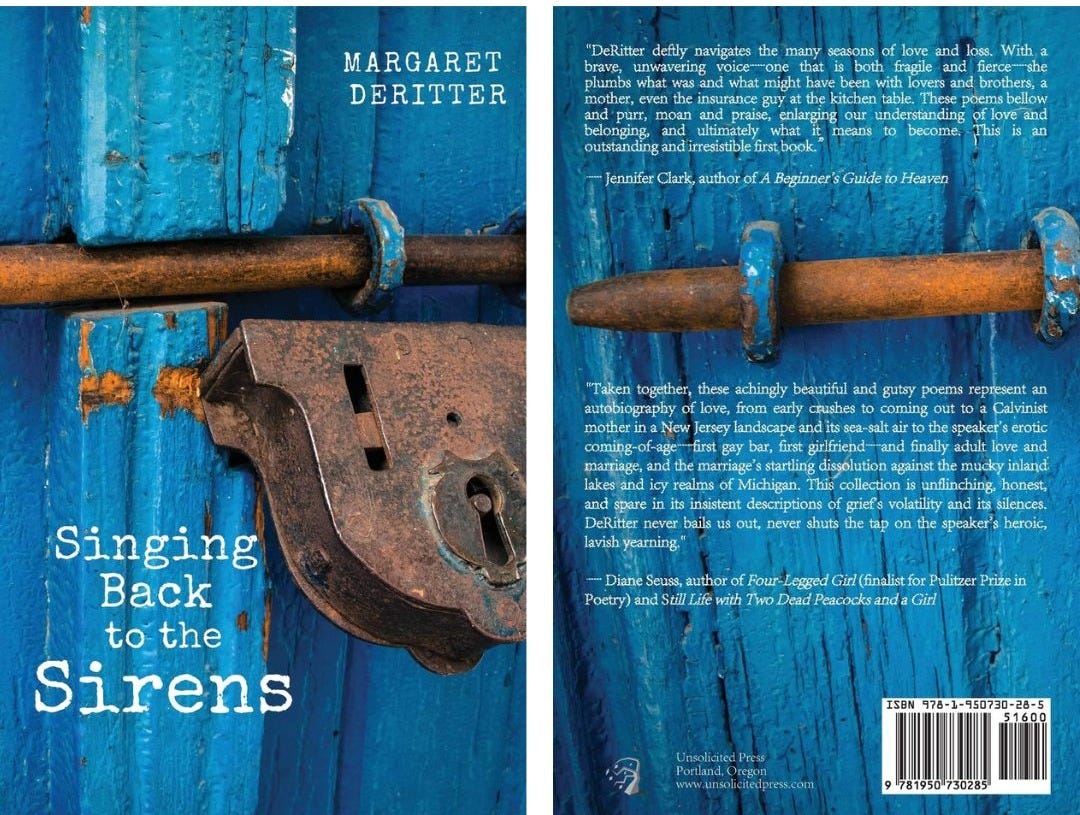

At the end of the reading, I invited questions from the audience. Margaret DeRitter’s hand shot up and she asked something like, “You wrote about several saints that never lived. How did the myths around these saints that never existed come into being?”

That was probably the “easiest” of the hard questions lobbed at me that evening.

Scraps of memories gathered over the course of seven years of researching saints scuttled across my synapses: something about a face, a town in Italy — oh, what was its name? … but because I couldn’t retrieve any of the information well enough to piece it together into a semi-coherent response, I just said, “I don’t know.” Margaret was definitely not satisfied.

I then shared a few of my thoughts on myths in general, but Margaret still didn’t seem satisfied.

Side note: Margaret is brilliant. She’s also a friend of mine who wrote a painfully beautiful poetry book that reads like a memoir. I highly recommend it.

Margaret’s question stayed with me. A few days later, I dug back into my research files and now, after hours of reading, I think I’ve pieced them together enough to give a decent response.

Muddled in myth

Saint Wilgefortis is a myth that grew out of misunderstanding.

Scholars trace the Wilgefortis legend back to Il Volto Santo di Lucca, which means the Holy Face of Lucca in Italian. (Hey, I was right in remembering it had something to do with a face!) Also known as the Black Christ of the Lucchesi, it is considered the oldest wooden sculpture in the Western world.

Ironically, this carving is bathed in several myths as well. Legend has it that Saint Nicodemus carved this eight-foot crucifix. Nicodemus may be familiar to you since he’s the guy who, according to the Gospel of John, showed up after Jesus’s crucifixion with a crap-load of myrrh and aloes and, along with Joseph of Arimathea (another saint), prepared Jesus's body and placed him in the tomb. As the story goes, Nicodemus apparently fell asleep before getting to Jesus’s head. When he awakened, he discovered it had been completed by an angel.

At some point, another miracle takes place and somehow the Holy Face sets sail from Palestine in a crewless ship and shows up in Lucca, a city in Tuscany, Italy.

Radiocarbon dating suggests that the Volto Santo was created between 770 and 880. Here’s an article (translated from Italian) about this recent discovery, and it includes a number of good photos, including a close up of the statue’s face, eyes clearly open.

Because the Jesus image is clad in a long wooden robe, scholars theorize that over time people mistook — quite eagerly, it seems to me — the image for a bearded woman wearing a dress. This interpretation was probably reinforced through the years by the practice of dressing up crucifixes, a custom which gained steam during the Middle Ages. To this day, there is an annual dressing ceremony of the Volto Santo that involves zhooshing up the Jesus statue with lavish textiles, jewelry, a gold crown, and keys to the city.

Art stirs and preserves myth

Hans Burgkmair the Elder (1473–1531), a German painter and woodcut printmaker known to make trips to Italy, created one of the earliest known artworks connecting the Volto Santo with Saint Wilgefortis. His woodblock, titled with the German name for Saint Wilgefortis (Saint Kümmernis), was printed around 1507. If you look closely, you’ll see that within the block itself are some words. These translate to “The Image of Luca.”

Eventually, the connection between Wilgefortis and the Volto Santo faded, but the growing body of artwork and the myth remained.

Wilgefortis was quite popular in her day. The bearded saint even hung in there long enough to make it into the first edition (published in 1812) of Grimms’ Fairy Tales as “Saint Kümmernis.”

Myth is a magnet for more myth

In some tellings of this legend, a fiddler plays for Wilgefortis as she is dying on a cross. As thanks, she kicks off a slipper to him. Later, when it’s discovered in the fiddler’s possession, it is assumed he stole it and he is sentenced to death. On his way to the gallows, he requests to play his fiddle one last time and his request is granted. As he is playing before Wilgefortis, the other slipper falls, thus proving his innocence.

Let’s cross our fingers that Margaret feels satisfied with this answer.

Image credits (in order of appearance):

— Cover image is from Europeana, Heilige Kümmernis by Müller und Sohn - The Photographic Archive of the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, Germany - CC BY-NC-SA. — Photos from the bookstore reading taken by Nancy Ablao. (Thank you, Nancy!) — Colored etching, "Saint Liberata (Uncumber, Wilgefortis)," artist unknown, courtesy of the Wellcome Collection, public domain. — Volto Santo, catedral de Lucca, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Volto_Santo_de_Lucca.JPG. — Woodcarving, Hans Burgkmair the Elder: St. Kümmernis, woodcut, Augsburg ca. 1507, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Ausschnitt_Burgkmair_Kuemmernis.JPG. — Heilige Wilgefortis oder Kümmernis - Museum Abtei Liesborn, Germany - CC BY-NC-SA. — “Saint Kümmernis,” a 1678 painting by unknown artist, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kuemmernis_museum_schwaebischgmuend.JPG. — “Heiliger Kümmernis” painted in 18th century by unknown artist, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hl_K%C3%BCmmernis_s%C3%BCddeutsch.jpg.

I love digging deeper, only to discover more questions.

Margaret IS brilliant!